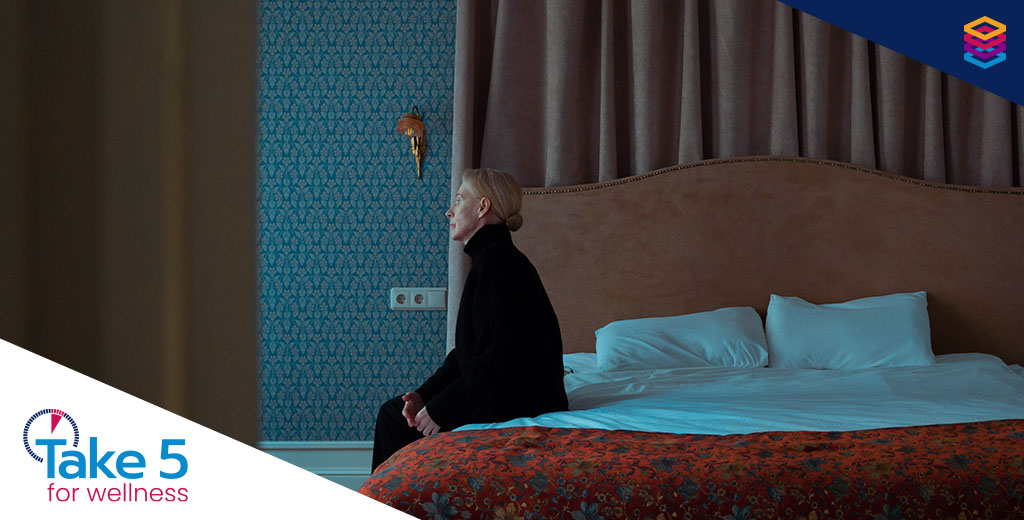

Donna Ferguson, a clinical psychologist, recalls working with a woman in her 50s who had gone on disability leave from an executive-level role. Her depression was so severe she couldn’t motivate herself to leave her bed. Recovery included a year of intensive therapy, working with Ferguson and a psychiatrist, and anti-depressant medication. She successfully returned to work and continues with regular maintenance therapy.

Mental-health challenges occur along a spectrum, from mild to moderate to severe. Those at the moderate level may start to have difficulty functioning at work, resulting in absenteeism or presenteeism, says Ferguson, who works in the Work Stress and Health program at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). People with severe mental health challenges struggle with long-standing conditions that clearly limit their functioning.

They “need an intense level of expert care in a safe environment to support them into recovery,” says Suanne Wong, Senior Director of Business Development Strategy and Operations at EHN Canada, a network of recovery centres that coordinates inpatient and outpatient care, and a preferred provider partner of Benefits Alliance.

Private health benefits plans are seeing more claims from plan members at the severe end of the mental-health spectrum, a trend that accelerated during the pandemic. Pre-pandemic, a Deloitte Canada report found that mental health issues already accounted for 30 to 40 per cent of short-term disability claims and 30 per cent of long-term (LTD) disability claims on average. Sun Life data since the pandemic shows a steady rise in LTD claims due to mental disorders. More are anxiety- or stress-related, which is worth noting because anxiety tends to be more chronic in nature than depression.

Disorders at the severe end of the spectrum require intensive and highly individualized treatment. Severe depression or anxiety may in some cases be linked to an eating disorder, an addiction, obsessive compulsive disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Roughly eight per cent of Canadian adults experience moderate to severe symptoms of PTSD, according to Statistics Canada, which also reports that approximately one million Canadians have a diagnosed eating disorder.

The risk of suicide is higher for people struggling with severe mental illness. Canada’s new 988 suicide prevention helpline has received roughly 1,000 calls and nearly 450 texts per day since it launched in late November, according to CAMH, which operates the line.

Treatment options

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a form of psychotherapy that has proven to be effective across the mental-health spectrum, says Ferguson. Another therapeutic approach, cognitive processing therapy (CPT), can be particularly effective for people dealing with PTSD or trauma. Ferguson also cites eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EDMR) and dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) as helpful for people with severe mental-health challenges.

While an employee assistance program (EAP) is a good start for mental healthcare at the mild to moderate end of the spectrum, and all employers should have one in place, it typically provides enough coverage for only a handful of sessions of mental-health counsel. “A few sessions of support are not meant to be for serious intervention,” says Ferguson.

The Canadian Psychological Association recommends an annual coverage maximum of between $3,500 and $4,000, enough to cover the cost of 15 to 20 sessions with mental-health practitioners. Ferguson says that’s generally sufficient for progress in moderate to severe cases, although more may be required where there are concurrent issues or comorbidities.

Ferguson adds it’s worthwhile to consider whether the coverage sufficiently provides for family members as well, who may be adversely affected by their loved one’s condition. Or vice versa: for example, a child with a severe mental illness can significantly impact the mental health, and productivity, of working parents.

Returning to work

The longer employees are on disability leave, the less likely they are to return to work, notes Wong. Early access to treatment programs can significantly reduce the duration of leaves and increase the likelihood of a successful return to work.

“If an employer has nothing to fill the gap between an EAP on the mild side and disability on the severe end, that’s where we’re seeing a lot of lost opportunity to better support employees and help them stay at work or get back to work faster,” says Wong.

Treatment programs break down into three categories: intensive outpatient, hybrid inpatient and outpatient, and inpatient. Intensive outpatient programs include several hours of therapy per week for weeks at a time, followed by months of after-care services. They can be effective for people with moderate to severe mental-health issues who want to continue to be with their family and maintain personal commitments.

Hybrid programs typically involve two weeks in an inpatient setting, such as a mental health hospital or private treatment centre, for those who require a short period of stabilization and round-the-clock support, followed by an intensive outpatient program.

For complicated disorders that require specialized approaches to treatment, inpatient programs typically require seven to nine weeks in an inpatient setting, followed by an outpatient program and after-care services.